Welcome to TEDMED conversations, where medicine, science, and the human experience meet the ideas shaping our future. In this episode, we explore one of the most urgent questions in health today.

What is the real promise of artificial intelligence in medicine, and what are the risks we can’t afford to ignore?

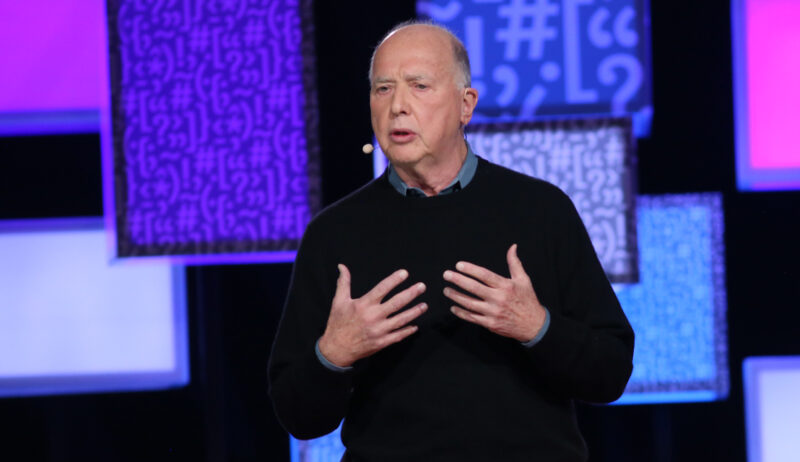

Hosting today’s conversation is Bruce Schneier, a renowned security technologist and author whose work has shaped how governments, companies, and societies think about trust, systems, and unintended consequences. For decades, Bruce has helped us understand not just what technology can do, but how it reshapes power, privacy, and responsibility.

Joining him is doctor Lina Nguyen, an emergency physician, public health leader, and former health commissioner of the city of Baltimore. Doctor Nguyen has spent her career at the intersection of medicine, policy, and public communication, advocating for care that is evidence based, equitable, and centered on people.

Together, Bruce and Doctor. Wen examine how AI is already transforming clinical decision making, diagnostics, and public health, while also raising critical questions about bias, accountability, trust, and the human role in care. This is not a debate about whether AI belongs in medicine, but a conversation about how it should be built, governed, and used.

This is TEDMED conversations.

So hi, Lina. Thanks for joining me. I’m really excited to talk about AI in health care. I wanna start with talking about what’s happening today. You know, where are the use cases? Where’s AI in health care that we don’t even see?

It’s such a great question, Bruce, and I’m so glad to be here with you to discuss this topic. I remember a few years ago, I was writing a column for the Washington Post about what I thought was going to be about the promises and perils of of using AI in health care and whether this is something that we should do. But once I started looking into this and interviewing experts, I realized that actually AI was well on the way to being incorporated into virtually every aspect of health care. It may not be exactly what we think of as AI immediately, but the landscape is very much that the AI revolution is already here.

There are some really good use cases, for example, in improving diagnosis. AI can serve as an extra pair of eyes to, improve diagnosis for abnormal findings and mammograms or colonoscopies. There have been some good studies demonstrating that it’s a good second opinion, second set of eyes for that purpose. Also, predictive algorithms are really useful, identifying, for example, which patients with pneumonia are most likely to deteriorate and to need a higher level of care or which patients with irregular heart rhythms could be safely sent home and which ones need to be hospitalized.

I think those are the use cases that are pretty well established. People are quite comfortable with them. But the question that remains is what about generative AI? And here too, there are some good use cases that are already being adopted, for example, in ambient AI, an AI that helps doctors to reduce their workload in writing the initial draft of notes.

But I think what chatbots can and cannot do for patients and also for clinicians remains to be seen.

So this is important. For a lot of people, AI equals chatbots. And most of the examples you gave are not generative AI. They’re not producing text.

They are predictive AI. They’re making decisions based on data. It’s really important that that people understand there’s more to AI than chatbots. That experience you had of looking at the future and finding it in the present is something I experienced in writing my book on AI and democracy.

Through the course of writing the book, I would write about things that are gonna happen in the future that have to revise it when there was an example of it happening in the present. And it’s always interesting to me to look at the different use cases and see where it’s working, where it’s not working so well. So how does that come out in medicine? Where are the good use cases where versus where are the not that great use cases yet?

Frankly, I think that we’re finding out in real time about what works and what doesn’t. There have been some really interesting studies done that show that certain forms of AI and here, we’re really talking about predictive AI, as you mentioned, to differentiate between predictive AI and generative AI. But here, we’re talking about uses of AI that could save lives. For example, there were studies done of hospitals that started using AI systems to get data in real time to figure out, well, how are patients doing?

What tests are showing that this patient isn’t looking so great? They may need to go to the intensive care unit. And how can we find those patients before, for example, the doctor has to look at all kinds of lab results and X rays and CT results, and they may not be able to get all these data in real time. They may be checking the lab results every two hours rather than literally right there and then.

And so there are systems in place that are already been incorporated, I think, that are great. I mean, I think we should be doing a lot more things like them that have the potential to to save lives. And there are very good examples too of AI that is starting to be incorporated in places where people really lack health care services. In countries, for example, where there aren’t enough obstetricians, there have been some studies looking at community health worker who is using an ultrasound that they learn after just a couple of hours, but then the images can be immediately interpreted using AI.

Are these images going to be as good as a radiologist or in the case, let’s say, of an obstetrician interpreting these results? Probably not. But is it better than nothing? Then certainly, yes.

Or also of AI being used for diagnosing tuberculosis in resource limited countries or interpreting slides to diagnose malaria. Similar cases, I think, where there is real potential, especially when you’re comparing it to really having no resources or no ability at all. Now I think where AI remains a lot more challenging and where I don’t think we have a good handle on how this could be used is regarding generative AI. I don’t think we are at the point yet where we can ask AI to truly triage patients.

Now this would be really useful if people can type their symptoms into AI and this algorithm can tell them, do you have to go to the ER right now? Can you go to urgent care? Can you wait until tomorrow or even five days from now to see your primary care physician? Is this something that you could treat at home?

I mean, that would be extremely useful and reduce resource utilization and also make sure that our ERs, for example, are used by patients who really need it the most. But I don’t think we are anywhere close to being there, and I don’t want patients to be replacing interactions with their physicians with AI just yet or with generative AI just yet.

And

when I think about AI doing a human task, I don’t necessarily think it’s going to do it better in in all dimensions. I think of it in terms of one of four, either speed, scale, scope, or sophistication. And you hit on, I think, all of those in how AI is being used in medicine. Sometimes it’s not better than a human doctor, but it’s faster, and speed is more important.

It’s sometimes the scale. We just don’t have a doctor in all of these locations, so AI maybe is a poor replacement for a doctor, but it’s a great replacement for no doctor.

There’s the scope, the fact that the AI could know more than any particular doctor. Then there’s sophistication. In some cases, the AI can make a more sophisticated diagnosis than a human can, like reading a test result.

And sort of interesting to watch those interplay as we look at AI either replacing or augmenting humans.

Totally spot on. I hadn’t thought about considering the uses of AI in quite this way, but I think we have to consider that AI is a tool. And therefore, as with any tool, there are reasons why we’re using it. We have to be clear about our objectives.

We have to understand also the limitations and the potential risks of the tools that we’re using as well. And I very much appreciated what you said about AI. And if we’re using it specifically for scale, maybe we recognize that the downside is it’s not as accurate as the ideal clinician, but it’s better than no clinician at all. And I think similarly in the case of rare diseases, I’ve also spoken with patient advocates and researchers in this space who are saying, look, the average physician, even a great clinician, isn’t possibly going to know all the manifestations of every disease that could possibly exist out there.

And in these cases, AI can be a really valuable second opinion of sorts. Often, are patients who got their diagnosis through AI. They then brought it up to their clinician who said, wow. I never heard about this before.

Let’s look it up together. And so I think that humility is also what’s necessary of our clinicians nowadays. I think the ones who are going to be really successful in incorporating AI because they can see it not as a threat, not as a menace, not as a replacement for them and their skills, but as an enhancement.

So let’s talk about AI making mistakes, and you alluded to that in a whole bunch of what you said.

I think it’s very context dependent. You talk about an AI reading a chest X-ray.

If it mistakes something that is malignant for benign, that’s potentially fatal. If it mistakes something that’s benign for malignant, that’s something that, you know, would be corrected in further tests.

If an AI makes a transcription error or it makes an error about what a certain, I don’t know, academic paper means, It could be potentially catastrophic, but humans make those same mistakes as well. Sometimes though, we hold the AI to a higher standard. Think about the debate about self driving cars. Humans are terrible drivers. We’re the worst drivers ever because we drink alcohol. But when an AI causes a crash, it’s a big deal. How does that play in the medical sphere?

I think that’s exactly right, Bruce. I think that we need to be understanding the standards that we’re holding AI to. And is it, for example, with health AI, are we holding AI to the standard of an expert clinician who is a specialist in this field, who has endless amounts of time to spend reviewing the medical record of the patient, and who has endless amount of time to spend discussing the results with the patient? If that’s the case, that standard is really high.

It’s also unrealistic for the vast majority of people in the US and certainly the vast majority of people around the world. But what exactly is good enough? And does good enough matter depending on the context as well? Should we hold the AI that people can access in the US to a higher standard than the AI that people can access in developing countries where resources are a lot more limited?

I mean, I think there are some ethical questions that that need to be resolved.

But in the meantime, I think that people can take heart in using AI as a compliment. I certainly think that there is a way for us to see in the future, perhaps, a different differentiation, if you will, as in the ideal medical care could be provided by the AI plus expert physician. Maybe the next level of care is AI plus clinician who is not necessarily a physician but who knows how to use AI tools. Maybe the next level is a clinician who’s not using AI. And then maybe the next level is AI alone. I mean, I think we’re already getting to this point where there is that differentiation, that hierarchy that exists.

I suspect that that hierarchy is going to increase disparities and increase inequalities. But at the same time, if we’re going to be increasing the level of care for everyone and if these levels of disparities already exist, I suppose there’s a question to be asked of, well, is this still the right thing to pursue if we’re able to improve the quality of care and the access to care, including for those who are the most vulnerable?

Yeah. I think this depends a lot on application. The question in general is AI going to increase or decrease power. So will it make the best clinicians or the best attorneys in another field, will it make them even better, or will it make the average clinician better?

Right? In the first case, you’re right. The rich get richer. Right? You have increasing capability and power.

If it is a more distributive technology, then it raises the ability for everyone to access medical care. In other fields, it it goes either way. In in programming, it seems that the best programmers can use the AI tools to be even better.

But in something like customer service, the AI doesn’t affect the best performance performance much, but raises the performance of the average. And my guess is in medicine, there’s a lot of different areas. We’re gonna see both of those things.

I think you’re right. If I have to predict as well, I think that the people who are expert diagnosticians who really value their own expertise might even struggle more with AI because they might not be willing to accept what AI is telling them because, hey. I have all this expertise. Why should I necessarily defer to AI or even listen to the second opinion that AI is offering?

But I think that there will be a generation there is a generation of clinicians who are very used to using computers and applications. And for them, really, they’re using AI throughout. I mean, I’ve talked to multiple clinician educators who are saying that they’re medical students and they’re residents, so people who are in medical training right now, The usage of AI in their every day is one hundred percent. It’s one hundred percent for things like administrative tasks, for drafting notes, for drafting emails, interpreting lab results, but also one hundred percent for seeking information.

Whereas in the past, we would use resources. And for example, you want to find out what are the antibiotics that I need to treat this type of pneumonia? Or what about this patient who has migraines for this amount of time who’s failed certain treatments? What do I do next?

You would have to read articles. You can consult, these reference guides. You’ll get the answer, but it will take you ten minutes. You might not get the most up to date answer.

But now there are ways to query this. And among the medical students or resident class, the the new generation, a hundred percent of them out of a hundred percent, I mean, they’re all using, these tools, these AI tools that already exist. And so I suspect to them we’re going to see an increase in level for the average clinician, if you will, for most people. Hopefully that also translates to better care for patients.

But I think, Bruce, there’s still a question that remains for me, which is an ethical question. It’s a value question for society, which is what’s the point of having better diagnoses and more accurate diagnoses if people still cannot afford their medications? As in you can have better diagnoses. You can you can raise the bar when it comes to accuracy, but is that necessarily going to translate to access?

I don’t think so. I think that’s something that we still have to focus on separately from this question of knowledge alone.

And you make a really good point that AI or any technology is not gonna solve the human problems. I wanna get back to something you said. I thought it was very insightful about the hierarchy of expert human with AI.

Under that is average human with AI. Under that is expert human without AI. Under that is, I guess, AI only. So interesting to me is that that hierarchy is fluid.

I think it’s gonna change. And the cautionary tale is chess. Right? Since the beginning of time until, you know, I forget the year, humans were the best at chess.

And then we saw a switch and the best AI could beat the best human, but still what could beat both of them was a team of a good AI and a good human. And that lasted a few years, and then suddenly the best AI now beats the human plus AI. And that’s gonna be true to the end of time. But as these technologies get better, I think you need to be prepared for shifts in where that hierarchy goes.

I totally agree with you, and I think that the medical profession and I’m sure many others, need to wrestle with how are we going to be training the next generation of clinicians so that they are humble, so that they remain open to change, so that they’re able to be flexible and adapt to this change in hierarchy and changes in skill and so that they acquire the necessary skills now but understanding that that will change. Now this isn’t new in medicine because there have been many advances. We no longer have so many open surgeries, for example. There are many surgeries that use robots and that use tiny little incisions as opposed to giant open incisions.

That’s something that surgeons have had to adapt to. I mean, are many examples of these huge changes in medicine, but I think that this is going to be one of them. And I do think that the clinicians who know how to use AI and are very comfortable with AI are going to replace the clinicians who are not. And I think to add to that that there’s going to be a new class of clinicians who will end up getting developed because the question needs to be raised of if we now or in the future have really sophisticated AI tools, do we really need so many specialist physicians who go through four years of undergraduate, four years of medical school, six potentially plus years of residency and fellowship and additional training, is that really necessary?

Maybe there’s going to be some class of clinicians whom are trained for three years instead of twelve years. And might that be another way for us to increase access?

It’s interesting. I think that is, part of trends we’re seeing today with RNs doing more doctoring things. It seems like you’re even more optimistic about AI than I am. And I think about AI in democracy, and I’m optimistic about the opportunities, but I also worry about the same technology in the hands of people who don’t have democracy’s best interest in heart can use the technology to subvert democracy.

It’s nice that in medicine, you kinda don’t have this class of doctors that secretly wanna kill their patients, which means you’re all on the same side of using this technology for good, for benefit.

So I wanna get back to your notion about there’ll be clinicians that will embrace it, clinicians that won’t, that some will fight it, and some will use it.

What advice do you give to a clinician that says, you know, I don’t wanna touch it. It’s all bad. I’ve read the news. It makes up stuff. It can’t do anything. What do you tell them?

I had not really thought about the point that you had raised about how in medicine, it seems like the optimism far outweighs the pessimism. I mean, I hear this among clinicians. I think, in general, we are very optimistic about the use cases for AI in medicine. I am certainly also very worried about AI’s use in other spheres, including the impact on democracy for all the reasons that you mentioned and all the things that you’ve written and and researched as well.

But I’m very positive about this one very specific use, which is in medicine. Does it outweigh the potential risks in other spheres? Probably not. But I think in this particular case, I am quite optimistic.

But going back to about

what is the advice for clinicians who are hesitant to use AI. One, I would say you’re already using AI. You probably may not be aware that you’re using AI, but when you use medical calculators to figure out if your patient should be hospitalized or do they likely have a pulmonary embolism or not, you’re using some form of AI, so you’re probably already using it. Second, if you want to get started, think about the use cases that can reduce your workload.

I think many physicians are afraid that this is just one more technology. They think about electronic medical records that were supposed to reduce their workload but actually added to it, and they fear that this could be that too. But look at the use cases of ambient AI that’s now allowed many clinicians to focus their time talking to patients, looking them in the eye and interacting with them rather than focusing on notes that will save them so much time at the end of the day that they have more time to spend with their patients. I mean, I think there are use cases like that that they can start with that they can then become more comfortable with because it will actually save them time and improve their relationship with with their patients and maybe with other people around them as well.

Then the third thing I would add is it’s not really a choice. I mean, this revolution of AI is already here. These clinicians, their students, their residents, their trainees are already using this technology. And for that reason alone, that should be enough for clinicians to say, I need to learn this too.

And here, the human processes matter. So you’re right that the AI can allow the doctor to spend more time with each patient and be a better doctor.

It can also allow the medical firm that employs the doctor to give the doctor twice as many patients, and it’s just as bad.

I think it’s important in all these applications to consider the power dynamics of the different humans and what they want out of this AI. The doctor’s gonna want better care. The firm is gonna want bigger profits.

You’re exactly right. And that’s certainly a concern that I’ve heard from many clinicians who say, I am cautiously optimistic. Right now, I love that I have all this time back. And I can be home in time for dinner with my family, and I don’t need to be spending two hours every night doing charting.

But if I have all this time back, are they just going to make me see more patients once they realize the the cost savings? I think that’s a real concern. I hear the similar concern for doctors who are now using AI for writing letters to insurance companies to approve medications for their patients. But these insurance companies are also now using AI to deny these same claims. And so is it going to be harder for clinicians and for patients to get through to somebody to talk to and the insurance company to make their case. That’s probably going to happen too. And so I do think that the guardrails have to be set, in a way that values people and doesn’t just benefit, large companies.

You know, my guess is in the future when the insurance company’s AI denies my claim, my advocacy AI is gonna argue with the insurance company AI, and they’ll have this massive AI argument, and they’ll figure it out. Will that be good? Will that be bad? I don’t know.

But not having to deal with it myself feels like a win.

So I wanna end by asking you about trust. I think a lot about AI trust and how to well, it’s usually phrased as get people to trust AI. I phrase it as ensure that AI is trustworthy.

And what I think about is integrity, the notion of data and computational integrity, and how do we build Entegris AI. It’s complicated. It’s there’s there’s a lot we don’t know, a lot of fundamental research that has to be done.

But when you think about trust, which feels just absolutely essential in all aspects of medicine, and AI, how do you think about how to get people to trust it more, which means how to get it to be more trustworthy?

I don’t think you can have trust without transparency.

So I think that transparency has to be a big part of it. That includes being very clear about how certain algorithms were developed. What were the data that went into this development? How was this algorithm tested?

Can the test be repeated? I think that adds to trust. I also think the usage can incorporate openness and transparency as well. I’ve talked to clinicians, for example, who very openly use AI with their patients.

This applies especially for rare diseases, as we talked about earlier, diseases that physicians don’t know very well, may have never treated, may have only read about in a textbook, but now they’re treating a patient who has this. I think it’s perfectly fine for the clinician to say and even advisable for the clinician to say, I don’t know about this, but I want to find out together with you. In the past, clinicians would have done this too by looking up online, showing a patient a paper, and saying, this is what I read. This is what I understand.

Let me share this with you. We could do the exact same thing when it comes to using AI together. And that’s something I would encourage patients to also do if they find information online through an AI, chatbot or through an online search or through looking up papers in their library, they they can also show those materials to their clinician and have an open conversation. I think that certainly this is not the only answer to how can we improve trust, but I think that transparency for how we develop tools and how we use AI will be essential if we want to have any element of trust in this technology.

So speaking from my position as a computer security person, I wanna tell you that transparency is just the first step. You want this to work, need transparency, oversight, and accountability. Because without those last two, then, you know, we just know stuff.

I’m trying to build systems that are trustworthy, you know, in all applications. So I like to think about those three things. So

we talked about doctors. Let’s talk about patients, about people, about us. What’s your advice to the average person about using this technology? Do you want them to open up a chatbot and ask medical questions? What do you want people to do?

With the technology that we have today, understanding that this could very well change with additional developments in the near future, I’d say that what these chatbots are most used for can be the most helpful with are understanding and interpreting information. So for example, you just went to the doctor, you received a new diagnosis, but you didn’t have enough time to ask all the questions there, or you thought of new questions. You can come back and ask the chatbot all the questions you can possibly imagine about what is this diagnosis? What should I expect, I just got prescribed this medication, what might the side effects be, when should I call the doctor, whatever questions you could possibly think of, this is a good use for it.

And asking it in different ways can also help as well. You can ask about it for yourself. You can ask about it for a friend that could give you additional information. Preparing for a doctor’s visit, it can be as useful there as well.

If you want to fine tune the questions that you have, knowing that you have limited time with your doctor, this is another potential use of of AI that’s very good. And lifestyle advice. AI can be helpful in drafting plans for diet, for fitness. If you want to go from couch to five k, it can create a pretty good program for that.

I think those are use cases that are pretty solid. Now I would be careful about diagnoses. I would not replace a clinician’s advice with AI, but you could ask AI chatbot for a second opinion. The more context you give it, the better.

So instead of just saying, why do I have a headache? You could say, I’m a thirty eight year old who has a ten year history of migraines. My migraine is worse now than usual. What should I be doing?

What kind of medications should I be asking for? I mean, the more context you give it, the better the answer is going to be. But always check it with your physician. You can bring the alternative diagnoses that the chat boss suggests to your clinician to consider.

But in all cases, you should not be replacing the clinician’s advice with the AI advice. And do not use AI if you have something that could be a medical emergency. If you have chest pain, weakness, numbness, stroke like symptoms, do not enter into the chatbot. Should I go into the ER, seek emergency medical attention right away?

So, Lina Nguyen, this has been absolutely fascinating and fantastic. To everyone, I just want you to make sure you know that this is changing all the time, that if we had this interview six months ago, would be different. And when we get back together six hours from now, it’s gonna be different again.

Thank you very much, Bruce. It was a pleasure chatting with you and learning from you as well.

You too.